I-Gear & AIDS:

I-Gear & AIDS:

Access to HIV /AIDS Educational

Websites in New York City Public Schools

A

WebQuest for 6th Grade (Communication Arts)

Designed

by

Jonathan

C Schleifer

mrschleifer@teacher.com

-Introduction:

You are public school teacher in

You are public school teacher in New York City V /AIDS prevention. You will review research that describes the

importance of access to information in HIV /AIDS prevention, review the New

York City Policy towards filtering Internet content, and test this policy by

trying to find websites that you can use to teach your students HIV /AIDS prevention. Once you have completed your research you

will draft an email to the New York City

-Task:

Once

you have completed your research you will draft an email to the New York City

Board of Education requesting that they change their filtering policy you will

include in it the reasons including HIV /AIDS educational resources as so

important and the list of sites that are blocked that need to be accessible.

-Process

& Resources: (please check

each box R as you complete it.)

Step 1:

q

With your

partner you will print worksheets 1 and 2. They will help you clearly define of the problem

(worksheet 1) and collect

evidence (worksheet 2)

q

Read the following World Wide Web pages

and answer the questions on worksheet #1. Only parts of the page will help you

answer this question so read carefully. Please pay attention to the parts that

focus on increased risks in adolescents. Because

these sites may be blocked in your school I have quoted them at the bottom of

this WebQuest in Appendixes I, II, and III.

Ä What

Are Adolescents' HIV Prevention Needs? (Appendix I)

Ä Early Sexual

Initiation and Subsequent Sex-Related Risks Among Urban Minority Youth: The

Reach for Health Study (Appendix II)

Ä New Study Examines Adolescents’ Use of the Internet for

Health Information (Appendix

III)

Step 3:

q

With your partner

you will print the following worksheet and read it will help you to evaluate current

public policies - Worksheet 4.

q

Read the

following World Wide Web pages and answer the questions on worksheet 4.

Ä The NYC Board of Education

Internet Acceptable Use Policy section on filtering

q

Use a common

search engine such as:

![]()

![]() Search for web sites that might provide information

for your students on HI

Search for web sites that might provide information

for your students on HI

Step 4:

q

With your

partner you will print the following worksheet and read it will help you to develop your own

public policies – Worksheet

5

q

Complete Worksheet 5

with your partner.

Step 5:

q

With your

partner you will print the following worksheet and it will help you to choose the best

solution – Worksheet

6.

q

Evaluate your

different policy recommendations and complete Worksheet 6.

Step 6:

Now that you have chosen the best solution you must

take action.

Write an email to the

Board of Education and propose your policy.

Explain clearly the faults in the current policy emphasizing your test

of the filtering software. Explain the dangers

of filtering this information from you students and advocate for you policy.

Ä

Members

of the Board of Education City of New York

-Evaluation:

|

|

Excellent 4 |

Good 3 (needs more work) |

Satisfactory 2(needs

a lot more work) |

Unacceptable 1 (needs to be redone) |

|

Define the problem |

Scholar stated the problem clearly and with some detail. |

Scholar stated the problem but without

detail. |

|

Scholar did not state the problem. |

|

Scholar identified the correct specific community location. |

Scholar did not identify the correct specific community location. |

|

Scholar did not identify any specific community location. |

|

|

Scholar identified three

undesirable social conditions that result from this problem |

Scholar identified two

undesirable social conditions that result from this problem |

Scholar identified one

undesirable social conditions that result from this problem |

Scholar did not

identify any undesirable

social conditions that result from this problem |

|

|

Gathering evidence of the problem |

Scholar presents three pieces of evidence that a problem exists. |

Scholar presents two

pieces of evidence

that a problem exists. |

Scholar presents one

pieces of evidence

that a problem exists. |

Scholar does not present any evidence that a problem exists. |

|

Evaluating

existing public policies |

Scholar has stated one of the major existing policies that attempts to deal with the social problem. |

|

|

Scholar has not

stated one of the major existing policies that attempts to deal with the

social problem. |

|

Scholar identified two or more advantages of this policy. |

Scholar identified one

of the advantages of this policy. |

|

Scholar identified two

or more advantages of this policy |

|

|

Scholar identified two

or more disadvantages of this policy. |

Scholar identified one

of the disadvantages of this policy. |

|

Scholar identified two

or more disadvantages of this policy. |

|

|

Scholar has stated whether the policy should be replaced, strengthened, or improved and supported their answer. |

Scholar has

stated whether the policy should be replaced, strengthened, or improved

but did not support their answer. |

|

Scholar has not

stated whether the policy should be replaced, strengthened, or improved. |

|

|

Developing public policy solutions |

Scholar has proposed at least three new/original public policy alternatives. (Scholar must elaborate on their new/original policies) |

Scholar has proposed two new/original public policy alternatives. (Scholar must elaborate on their new/original policies) |

Scholar has proposed one new/original public policy alternatives. (Scholar must elaborate on their new/original policy) |

Scholar has not proposed new/original public policy

alternatives. |

|

Selecting the best public policy solution |

Scholar has chosen between

the alternative policies they created and defended their choice. |

Scholar has chosen

between the alternative policies they created but did not defend their

choice. |

|

Scholar has not

chosen between the alternative policies they created. |

-Conclusion:

In

this WebQuest you have studied the policies of the New York City

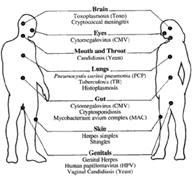

-Image

Sources: Give ©redit

where ¢redit is due.

1.

www.urmc.rochester.edu/

strong/AIDS/aidspg.htm

2.

http://www.aegis.com/topics/oi/

3.

www.cdc.gov/od/admh/

health.htm

4.

pravda.ru/main/2001/

08/24/31067.html

-New York State

E1c

Read and comprehend informational materials.

E1d Demonstrate familiarity with a

variety of public documents.

E1e Demonstrate familiarity with a variety of

functional documents.

E2a

Produce a report of information.

E2e Produce a persuasive essay.

E3b

Participate in group meetings

E3b

Participate in group meetings

E4b

Analyze and subsequently revise work to improve its clarity and effectiveness.

-Appendix

I

The

following is found at

http://www.caps.ucsf.edu/adolrev.html

What

Are Adolescents' HI

What

Are Adolescents' HIV Prevention Needs?

(updated 4/99)

Can adolescents get HIV ?

Unfortunately, yes. HI

Unprotected sexual intercourse puts young people at risk not only for HI

Some sexually-active young African-American and

What puts adolescents at risk?

Adolescence is a developmental period marked by discovery and experimentation that comes with a myriad of physical and emotional changes. Sexual behavior and/or drug use are often a part of this exploration. During this time of growth and change, young people get mixed messages. Teens are urged to remain abstinent while surrounded by images on television, movies and magazines of glamorous people having sex, smoking and drinking. Double standards exist for girls-who are expected to remain virgins-and boys-who are pressured to prove their manhood through sexual activity and aggressiveness. And in the name of culture, religion or morality, young people are often denied access to information about their bodies and health risks that can help keep them safe. 5

A recent national survey of teens in school showed that from 1991 to 1997, the prevalence of sexually activity decreased 15% for male students, 13% for White students and 11% for African-American students. However, sexual experience among female students and Latino students did not decrease. Condom use increased 23% among sexually active students. However, only about half of sexually active students (57%) used condoms during their last sexual intercourse. 6

Not all adolescents are equally at risk for HI

Can education help?

Yes. Schools are an important venue for educating teenagers

on many kinds of health risks, including HI

Are schools the only answer?

No. Young people need to get prevention messages in lots of

different ways and in lots of different settings. Schools alone can't do the

job. In the

Youth who are not in school have higher frequencies of behaviors that put

them at risk for HI

Programs targeting hard-to-reach adolescents at high risk for HI

Families play an important role in helping teenagers avoid risk behaviors.

Frank discussions between parents and adolescent children about condoms can

lead teens to adopt behaviors that will prevent them from getting HI

The WEHO Lounge in

Project

What needs to be done?

HI

Any program for adolescents should be interesting, fun and interactive, and

involve youth in the planning and implementation. This is especially true for

out-of-the-mainstream youth and youth from diverse cultures. Programs for hard-to-reach

youth who are most at risk for HI

Says who?

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Young people at

risk-epidemic shifts further toward young women and minorities. Fact sheet prepared by the CDC. July 1998.

2. Eng TR,

3.

4. Miller KS, Clark LF, Moore JS. Sexual

initiation with older male partners and subsequent HI

5. UNAIDS. Force for Change: World AIDS Campaign with Young

People. Report prepared by UNAIDS, The Joint United Nations Programme

on HI

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends

in sexual risk behaviors among high school students-United States, 1991-1997.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1998;47:749-752.

7. Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mahler KA,

Rosario M. AIDS prevention with adolescents. AIDS

Education and Prevention. 1995;7:320-336.

8. UNAIDS. Impact of HI

9. Pinkerton SD, Cecil H, Holtgrave

D.R. HI

10. Associated Press. Sex education that teaches abstinence wins

support. New York Times.

11. Jemmott JB, Jemmott

LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HI

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health risk behaviors among adolescents who do and do not attend

school-United States, 1992. Morbidity and Mortality

Weekly Report. 1994;43:129-132.

13. Zibalese-Crawford M. A creative

approach to HI

14. Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, et al. Patterns of condom

use among adolescents: the impact of mother-adolescent communication. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1542-1544.

15. Weinstein M, Farthing C, Portillo T, et al. Taking it to the

streets: HI

16. Harper GW, Contreras R,

Prepared by Gary

W. Harper, PhD MPH* and Pamela DeCarlo**

*Department of Psychology,

April 1999. Fact Sheet #9ER

Reproduction of this text is encouraged;

however, copies may not be sold, and the Center for AIDS Prevention Studies at

the

![]() Return

to Fact Sheets main page

Return

to Fact Sheets main page

-----------------------------------------------

-Appendix

II

The

following is found at http://www.thebody.com/siecus/middle_school_behavior.html

|

SHOP

Talk: School Health Opportunities and Progress Bulletin |

||

Early Sexual Initiation and Subsequent Sex-Related Risks Among Urban Minority Youth: The Reach for Health StudyFamily Planning Perspectives recently published results from the Reach for Health (RFH) Study that examines early sexual initiation and its possible relationships to risky sexual behaviors among urban minority youth. The study included 1,287 minority seventh graders who attended one of

three participating middle schools in ResultsEver Had IntercourseMales

Females

Had "Recent" IntercourseMales

Females

Males

Females

Used a Condom Less Than Half of the TimeMales

Females

Involved in PregnancyMales

Females

Males

Females

10th Grade Population OnlyHad 4 or More Sex Partners

Was Drunk/High During Sex

The authors note that although youth who initiate intercourse early may have more experience, they do not use condoms more consistently. These same youth also experience a disproportionate number of pregnancies. They point out that the health and social consequences of early sexual onset are not equally distributed nationally among youth. According to the authors, the chance that a white adolescent experiences his or her first intercourse at the ages commonly reported in this sample is small. Therefore, they believe, it is clear that early sexual initiation and its subsequent pattern of risk-taking have not been receiving the attention they deserve or would get if the behaviors were more prevalent in wealthier communities. The authors believe the assumption that early adolescents are not sexually active has resulted in serious limitations on what prevention and intervention programs can address at different developmental stages. They think a fuller understanding of various cultures, including gender roles and their link to early sexual experimentation, are essential for the development of programs that address the needs of both males and females from minority communities. For more information: L. O’Donnell, et al., “Early Sexual Initiation and Subsequent Sex-Related Risks Among Urban Minority Youth: The Reach for Health Study,” Family Planning Perspectives, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 268-75. |

||

This document was provided by The Sexuality Information

and Education Council.

-----------------------------------------------

-Appendix III

The

following is found at http://www.thebody.com/siecus/internet.html

|

SHOP

Talk: School Health Opportunities and Progress Bulletin |

||

New Study Examines Adolescents’ Use of the Internet for Health InformationA study in the July issue of the Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine examines adolescents' use of and attitudes toward accessing health information through the Internet. Researchers surveyed 412 tenth grade students in an economically and ethnically diverse suburban town. The survey focused on three health areas: birth control and safer sex; diet, nutrition, and exercise; and dating and family violence. Students were asked what health topics they had ever tried to obtain information on from the Internet, what topics they obtained "the most information on from the Internet," and whether they thought the Internet was worthwhile, trustworthy, useful, and relevant. Internet Use

Where Teens Get InformationRespondents were asked which of 15 possible sources they used for health information. They could name more than one source. Among responses:

|

||

This document was provided by The Sexuality Information

and Education Council.